Meteorites discovered on Earth may have come from Mercury, scientists say

Rocks found on Earth may have originated from Mercury: a potential breakthrough for astronomers.

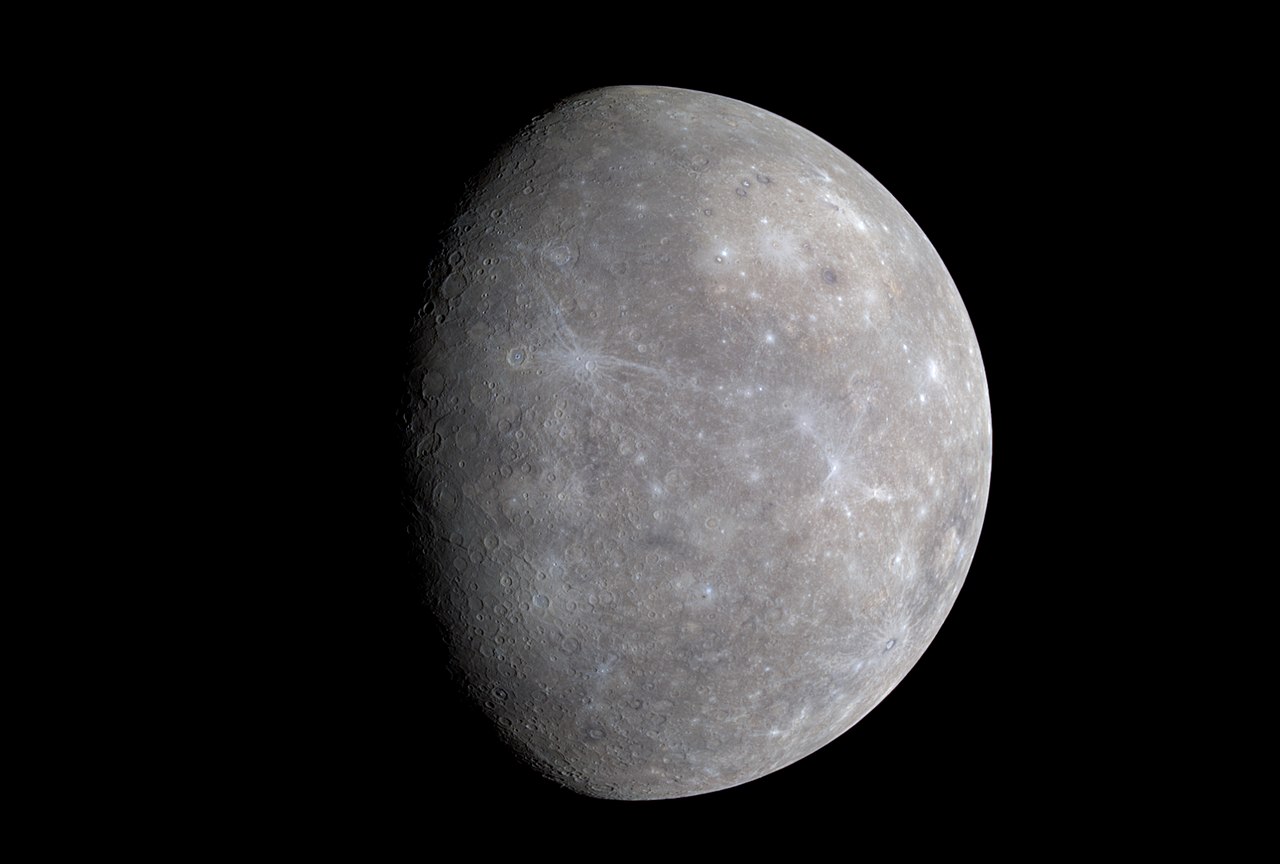

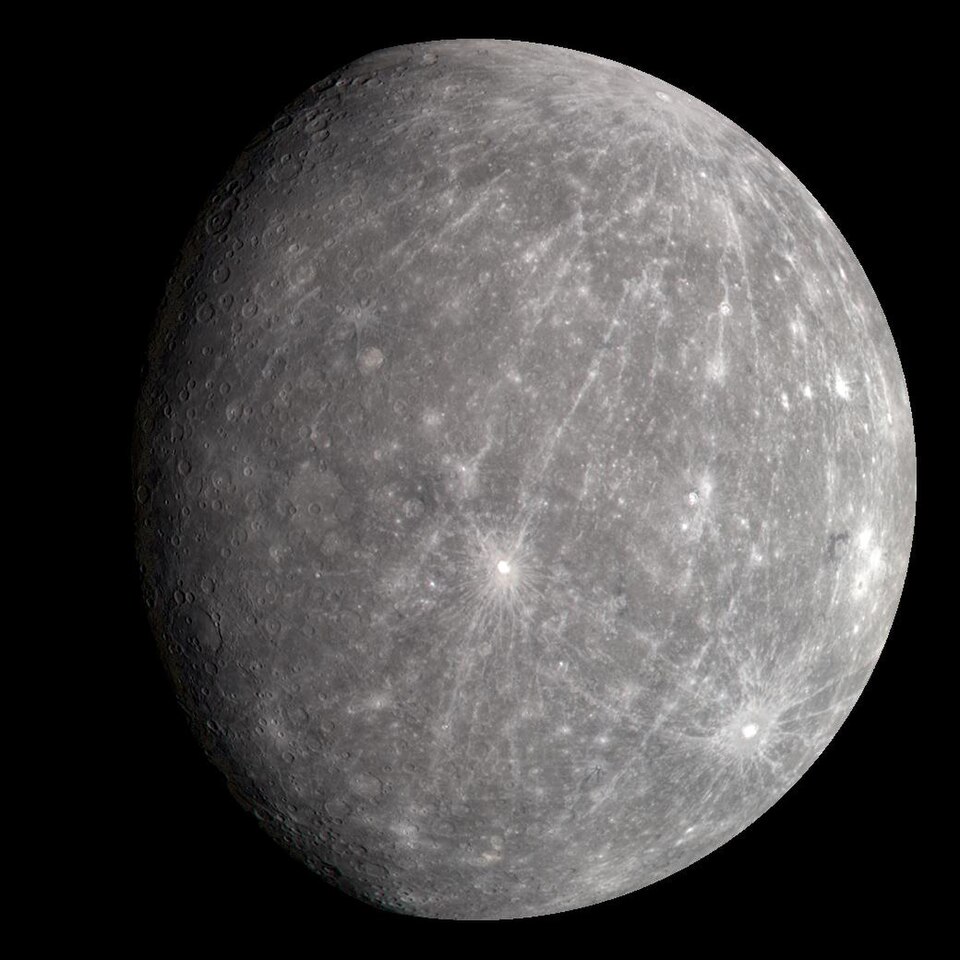

Although two space probes (Mariner 10 and MESSENGER) have visited Mercury, no controlled landing has ever taken place on the planet‘s surface, aside from one intentional crash. A mission to land there would be both complex and costly, taking an average of seven years to reach the planet.

The probes studied Mercury’s surface composition from orbit, which has helped scientists determine whether any meteorites might come from the planet. However, the composition of candidate space rocks has never matched Mercury’s profile, until now, according to a new study published in Icarus.

“Our latest study investigated the properties of two unusual meteorites, Ksar Ghilane 022 and Northwest Africa 15915,” said Ben Rider-Stokes, a postdoctoral researcher specialising in achondrite meteorites at The Open University, in a piece he wrote for The Conversation. “We found that the two samples appear to be related, probably originating from the same parent body. Their mineralogy and surface composition also exhibit intriguing similarities to Mercury’s crust. So this has prompted us to speculate about a possible Mercurian origin.”

Both meteorites contain olivine and pyroxene, along with smaller amounts of albitic plagioclase and oldhamite. According to the research team, this matches predictions about Mercury’s surface makeup. Still, there are puzzling inconsistencies.

Nothing is certain yet

“Both meteorites contain only trace amounts of plagioclase, in contrast to Mercury’s surface, which is estimated to contain over 37%,” Rider-Stokes noted. He also pointed out that the samples have been dated to 4.528 billion years. That presents a problem, as estimates suggest Mercury’s surface formed between 4 and 4.1 billion years ago.

“If the oldest surface visible on Mercury is 4 billion or 4.1 billion years old, then that would imply that the first perhaps 500 million or 400 million years of the planet have been erased,” explained Simone Marchi, a planetary scientist at NASA’s Lunar Science Institute, in a 2013 interview with Space.com. “They are gone. There is no record of the oldest surface of Mercury, and we expect that Mercury pretty much formed like the Earth or the Moon around 4.5 billion years ago.”

Rider-Stokes and his team say this doesn’t necessarily rule out a Mercurian origin. “If these meteorites do originate from Mercury, they may represent early material that is no longer preserved in the planet’s current surface geology,” he said.

Why Mercury is so hard to study

Despite being much closer to Earth than Jupiter or Saturn, reaching Mercury is actually more difficult, according to the European Space Agency (ESA). Some estimates suggest that reaching the dwarf planet Pluto requires less energy than getting to Mercury. The challenge lies in Mercury’s proximity to the Sun. Any spacecraft aiming to orbit Mercury, instead of just flying past it, must constantly brake against the Sun’s gravitational pull.

“There are two ways how to accomplish this braking,” said Johannes Benkhoff, ESA project scientist for the BepiColombo mission. “You either need a huge spacecraft that carries a lot of fuel, or you can use the gravity of other planets to slow you down along the way. To reach Mercury, you need to perform multiple such planetary flybys and so the journey takes a long time.”

Additionally, the intense heat near Mercury poses a major obstacle, with temperatures high enough to melt lead.

That’s why finding a piece of Mercury here on Earth would be so valuable. Just as we’ve found meteorites from Mars and the Moon, asteroids crashing into Mercury can sometimes eject debris into space, potentially forming new asteroids. Yet no meteorite has ever been definitively proven to originate from Mercury—a puzzle the study’s authors call “a long-standing mystery.”

To read or share this article in Hungarian, click here: Helló Magyar

Read more space news on Daily News Hungary!

Read also: