Five historic March 15th celebrations in Hungary

15 March remains one of the most significant dates in modern Hungarian history. While it is widely accepted today as a national holiday commemorating the 1848-49 Revolution and War of Independence, this was not always the case. In fact, there were times when celebrating 15 March was downright dangerous. The ruling authorities often viewed these commemorations with suspicion. Here, we recount five particularly memorable 15 March’s .

Before the Austro-Hungarian compromise: The bloody suppression of 1860

Following the defeat of the 1848-49 Revolution and War of Independence, 15 March became an unwelcome anniversary for those in power. Like other symbols of the revolution, the holiday was suppressed, and those who chose to commemorate it faced severe repercussions. Nevertheless, reverence for this date never disappeared.

In fact, it became a form of resistance against the absolutist regime.

On 15 March 1860, students and citizens of Pest organised a large-scale commemoration. The timing was significant: in 1859, Austria suffered a crushing defeat against the Franco-Piedmontese alliance at Magenta and Solferino, forcing Emperor Franz Joseph to reluctantly accept a ceasefire. Austria lost control over Lombardy, and shortly before 15 March, Habsburg archdukes were driven out of Northern Italy. These events emboldened the revolution’s supporters while making the authorities increasingly wary.

The young activists first attempted to hold a memorial mass for fallen freedom fighters at the city’s central parish church and later at the Franciscan monastery, but both requests were denied. Eventually, they were able to hold a service at the Calvinist church on Kálvin Square, where they sang the patriotic anthem “Szózat.” The crowd then proceeded toward the cemetery in Ferencváros (near today’s Saint Vincent de Paul Church at the intersection of Mester and Haller streets), only to find it blockaded by authorities. Some individuals were singled out from the group, prompting the rest to head to Kerepesi Cemetery (now Fiumei Road Cemetery), which was also cordoned off.

When the crowd hurled wreaths over the cemetery walls, soldiers opened fire on the demonstrators.

Three people were wounded, including law student Géza Forinyák, who succumbed to his injuries two weeks later, becoming a martyr of 15 March. While only a few hundred had participated in the original wreath-laying, tens of thousands attended his funeral.

15 March in the Horthy Era: A violent crackdown

Even after the 1867 Compromise between Hungary and Austria, April 11—marking the enactment of the April Laws—was considered the official holiday of the revolution, as it was a less contentious date for Franz Joseph. Nonetheless, pro-independence supporters continued to honor 15 March. This remained the case during the Horthy era, although it was only officially recognised as a holiday in 1927. However, commemorations often focused on the memory of Arad, Világos, and even the Treaty of Trianon rather than the original revolutionary events. (A legal trial even arose over the interpretation of 1848.)

On 15 March 1942, commemorations turned into a widespread anti-war demonstration.

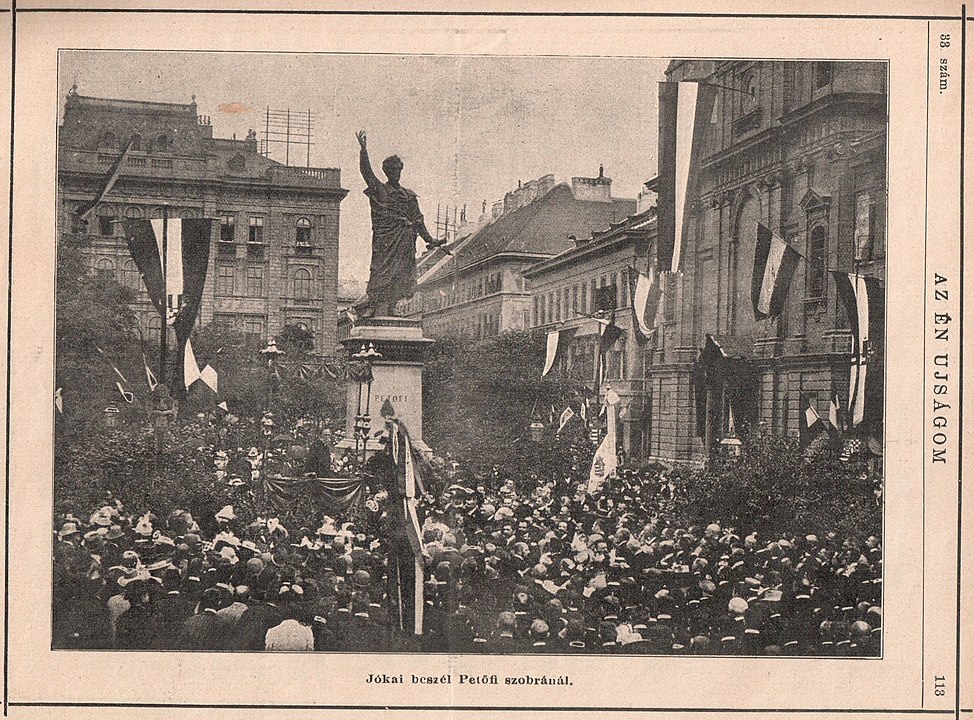

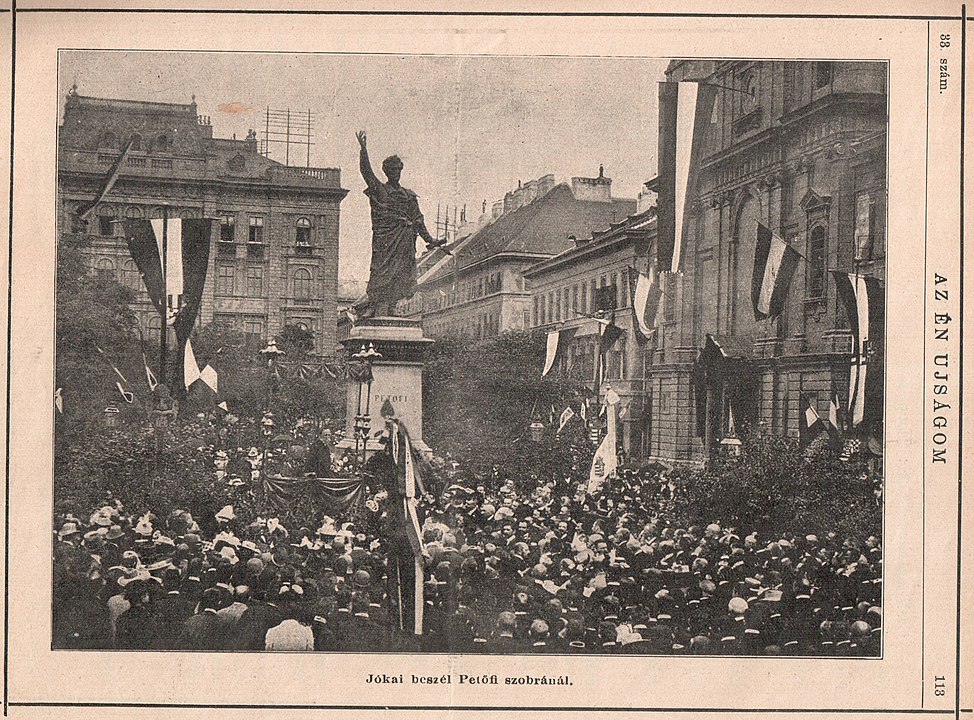

Surprisingly to many today, both Social Democrats and Communists embraced 15 March as their own. They frequently held wreath-laying ceremonies and mass rallies in its honor. Growing dissatisfaction with World War II led them to unite with anti-German right-wing politicians for the occasion. The Hungarian Historical Memorial Committee organised an event at the Petőfi statue in Budapest, drawing a broad anti-war coalition, including figures like Endre Bajcsy-Zsilinszky and Árpád Szakasits.

However, police forces brutally dispersed the crowd with mounted units wielding sabers. Ninety individuals were arrested following the protest.

15 March: A crisis for the communist regime

In 1948, the Communist government used the centennial anniversary for its own propaganda purposes, but by 1951, it had demoted 15 March to a regular working day (though schools were still closed). After the suppression of the 1956 revolution, the new Kádár regime closely monitored commemorations, determined to quash any revolutionary sentiment. One tactic was to merge 15 March with Communist anniversaries. From the late 1960s, it was incorporated into the “Revolutionary Youth Days,” alongside 21 March (marking the Hungarian Soviet Republic) and April 4 (celebrating Soviet liberation). The latter dates received far more emphasis in official events.

But this dull, state-controlled observance failed to satisfy Hungary’s youth.

By 1971, surprisingly powerful protests erupted.

Young demonstrators gathered at the Petőfi statue, but police quickly broke up the event. However, crowds continued to assemble at various locations across the city. Authorities responded with brutality, severely beating multiple attendees. Twenty people were detained, and several were arrested. They were later sentenced on dubious charges, including pulling up red flags at the Petőfi statue and distributing tricolor armbands.

Renewed protests in the 1970s

By 1972, demonstrations had escalated. The crowd moved from 15 March Square and the official Communist youth initiations at Batthyány Eternal Flame to the National Museum Garden, planning to march to the Petőfi statue via Astoria and Kossuth Lajos Street. However, police blocked their path at Astoria. That evening, demonstrators regrouped in the Castle District.

At Matthias Church, police once again dispersed the gathering.

Eighty-eight people were arrested in connection with the protests, many of whom later faced fabricated legal charges. Students and young professionals were expelled from universities, and 15 were given prison sentences. Inside the ruling Communist Party, concerns were raised about the government’s handling of the situation.

The “battle of Chain Bridge”

These tactics ultimately succeeded. After 1973, major protests ceased for over a decade. Smaller demonstrations did take place, but they were no longer tied explicitly to 15 March. That changed in 1986.

That afternoon, thousands gathered at the Petőfi statue after official events ended. A crowd of about one thousand then marched to Kossuth Square and the Batthyány Eternal Flame before crossing to Buda to the Bem statue, singing the national anthem at each stop. When they reached the Kölcsey statue at Batthyány Square, police dispersed them.

By evening, another group had assembled at the Petőfi statue. As they attempted to march to the Táncsics statue in the Castle District, they were herded into a trap.

At Chain Bridge, security forces blocked both ends. Protesters were beaten with batons, arrested, or had their identification documents confiscated.

State-controlled media remained largely silent, but Radio Free Europe and underground samizdat publications reported the events. As a result, 15 March regained its status as a platform for opposition protests—though as Hungary moved toward regime change, these demonstrations increasingly took on a more peaceful tone.

To read or share this article in Hungarian, click here: Helló Magyar

Read also:

- Traffic in Budapest will turn upside down on 15 March: airport express bus affected

- The ruined castle of the “most Hungarian” Habsburg near Budapest